My gravel bike is like a self-service shop—

not just for me … 😊

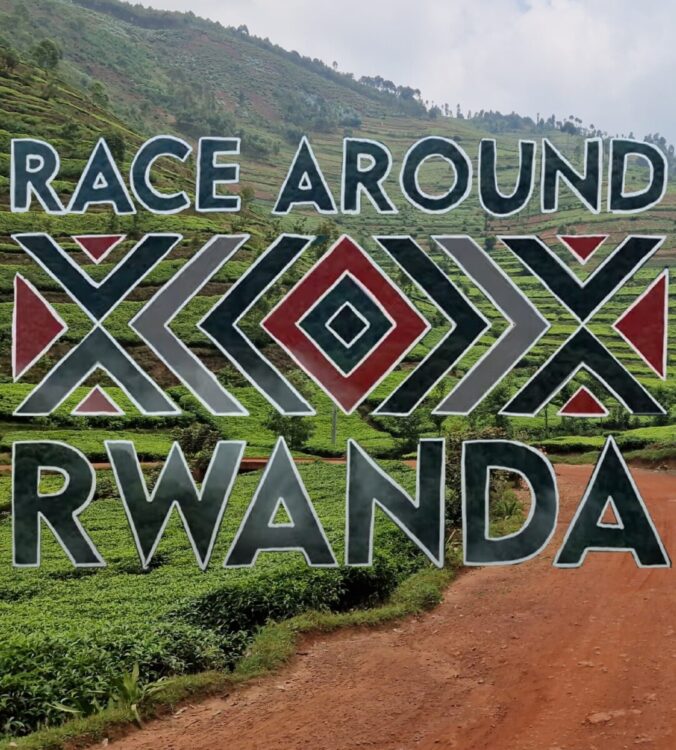

I was certainly brave when I signed up for the Race around Rwanda. I already had a feeling that the African adventure would be something truly special.

In short, the race is a 1,000-kilometer loop around this East African country on the equator, with a total of 18,000 meters of elevation to conquer. Rwanda isn’t called „The Land of a Thousand Hills“ for nothing.

Curious? First, here’s my video covering the entire race. If you prefer reading the report, each day begins with a short video.

Day 1:

Start in Kigali – CP1 Lake Muhazi – Gasange

210 km/ 2850 Hm

Time in Motion: 11:30h

Elapsed Time: 14:07h

My Video – day 1

Race Day Morning

My excitement is building. A wonderful breakfast has been prepared for us at Café Tugende. Last preparations before the start. Someone informs me that my tracker appears as not fully charged on the Legends Tracking page, so I plug it into the nearest available socket again; someone else must have had the same idea. One last trip to the restroom, tracker packed, and I line up at the start. A cheerful blinking of red rear lights, and the blue flashing lights of the police car escorting us out of the city for the first few kilometers. Countdown … and we’re off! The tension fades with the first pedal strokes. There’s no turning back now … Whatever comes, comes!

@mozay_dufitumukiza

23 kilometers of asphalt, interrupted by about two kilometers of rough cobblestones. This is where you can tell who hasn’t secured their gear properly. A rear light, a pair of sunglasses, and water bottles lose their owners. I get shaken up quite a bit, but everything stays in place.

Shortly before six, daylight breaks. Near the equator, this happens within minutes—pitch dark to sunrise, almost like someone flipping a light switch. Then it stays light for 12 hours before the same rapid transition back to darkness. So, time to pedal hard—I had decided to ride only during daylight. As a woman cycling alone, I do feel a bit uneasy riding in the dark, even though Rwanda is considered one of the safest countries in the world.

At dawn, we hit the first gravel section. Simon describes it as “smooth.” At times, though, it’s quite rough—so what will the sections without this description be like?

It’s still early in the morning, and it’s also Sunday, yet so many people are already on the move: walking along the roadside, riding heavily loaded bicycles, and, of course, moto-taxis—like EVERYWHERE. This won’t change in the coming days. There is hardly a kilometer where no one is around.

I greet left and right with „Salama“, believing it meant „Hello“. Only after returning home does AI inform me that „Salama“ is actually a Swahili expression for well-being, similar to „All good?“ or „Stay healthy“. The people were always surprised by my greeting but responded cheerfully—sometimes with „Komera“, which means „Stay strong, have strength“, or with „Yego“—Yes!

For nearly 60 kilometers, I am accompanied by reddish-brown, compacted earth. Even though it’s dry—or perhaps because of that—my legs soon become coated in a thick layer of reddish dust, mixed with sweat and sunscreen. My clothes, too, quickly lose their original color. By midday, I already feel a connection with the people here, especially the children, whose clothes are not always spotless. Water, it seems, is often needed for more important things than washing and personal hygiene. It’s not always available as we know it—just turning on a tap and having cool water flow. No, here it often has to be fetched from far away. You frequently see women, men, and children carrying yellow jerrycans, hauling the full containers home—often on their heads or pushing them up steep hills on overloaded bicycles.

At CP1, I long for a quick freshen-up—a chance to cool down and clean my legs, arms, and face. But no luck. Water, like in much of the country, is scarce—at least for something as trivial as washing off dust. But does that even matter? In the coming days, I will learn that there are far more important things, like having enough water to drink.

After nearly 80 kilometers, we return to asphalt. I stop briefly by a small group of children selling bananas. A whole bunch—if that’s what it’s called—costs 300 Rwandan Francs. I only need three bananas and pay with a 1000 Franc bill. The money is snatched from my hand and disappears—no change is given. 1000 Francs is worth just around 70 cents. The children immediately surround me, asking for more money. I move on.

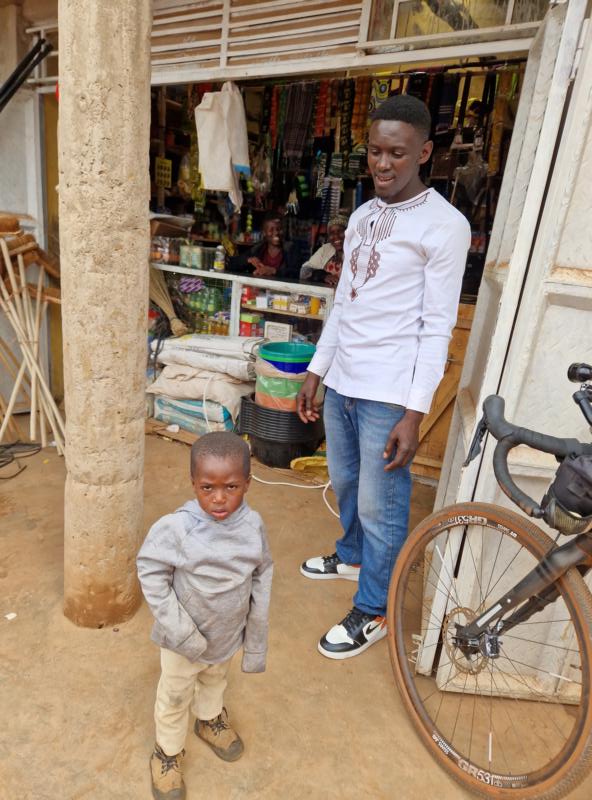

Shortly afterward, I reach a cyclist hotspot—there must be something here! Yes, a shop!

Every few kilometers, there are small roadside villages. Here, not only are there even more people, but also small “shops.” I could have saved myself a lot of detailed planning—shop? You get what they have: Water—always. Fanta—always. (They distinguish between Fanta Orange, Fanta Lemon, and Fanta Cola—sometimes even Fanta Pineapple.) Some kind of cookies is always available, or Chapati and Mandazi—East African pastries, often eaten as snacks or sides, likely baked by women early in the morning and transported in large transparent buckets to their shop destinations. Chapati is a flatbread fried in a pan, while Mandazi are slightly sweet, deep-fried dough balls. At first, I was hesitant to try these energy-packed snacks.

I refill my water reserves—it has gotten very hot, and my thirst is greater than usual. I treat myself to a cola. Then, I make an unfortunate discovery: my little white plush bear, which has accompanied me on all my bikepacking adventures, is gone. Likely torn off during my stop with the kids. I hope it makes a Rwandan child happy! Goodbye, little bear!

After a rapid descent, we hit gravel again—smooth and flat. With a slight tailwind, I speed through this low-lying, intensely hot region. It’s midday, and the moving air offers a little relief.

This changes after about 50 kilometers—now it’s time to tackle some climbs. No more cooling breeze, just the scorching sun at 38°C in the shade. Coming from winter, this heat is brutal. My head feels like a burning furnace.

One experience makes me unable to ride around as carefree as before:

In front of me, four children (let’s call them almost adolescents) sit down in the middle of the road, forming a barrier with their legs spread apart. When I brake, they jump up and surround me. They ask for „money“ in a more aggressive tone, and when I try to keep riding, they grab and tug at my bike.

Later in the evening, I’ll read in the WhatsApp group that some people’s rear lights have gone missing. Ah, so that’s what the kids were after… But my lights were secured with zip ties—not against children, but to prevent them from getting lost.

Otherwise, only happy faces—everyone greeted me back, and some children called out „give me money!“ or simply „good morning“ and „how are you?“

Eventually, I make it and roll into the first checkpoint around 3 PM. A crew member immediately informs me that my tracker isn’t working properly and gives me a new one. Lars also tells me that, according to Legends Tracking, I am still in Kigali. They must be worried back home. I try to reassure everyone via WhatsApp, only to realize I have no internet connection.

I’m starving and dive into the lunch spread: vegetables, rice, pasta, sauce, fries, water, and—once again—Fanta. I also want to wash up. No luck. There is a basic toilet, but no running water.

It’s getting late, and I need to find a place to sleep. The afternoon is slipping away. Back home, I had noted a few options, but to my dismay, they are all fully booked. What now?

I decide to continue riding with some others who have the same problem. Piotr wants to go all the way to Byumba—another 90 kilometers from CP1, with several small climbs and one long ascent of nearly 1000 meters elevation gain. Definitely too far for me.

On the way, I solve my internet problem. I stop at one of the yellow umbrellas found in every village, bearing the logo of the telecom provider whose SIM card we received from the event organizers. I struggle to explain that I have no internet. After some effort, the woman under the umbrella uncovers my own technical stupidity—I had simply forgotten to enable data roaming.

Relieved, I ride on. Soon, a beep—a message comes through. I have reception again! Lars texts me that he has found accommodation in the next village. I arrive shortly after, and we inspect the place. Before that, I quickly text Hermann to let him know I’m on the move and no longer in Kigali.

The accommodations initially shock me. The „bathroom“ especially: a plastic toilet, and a yellow jerrycan next to it is presumably meant to serve as the flushing mechanism. Two rooms, the bedding rumpled and not entirely clean. At least there’s water, with a tap next to the entrance door. The host seems to have moved his family out? I’m not sure, as there are no personal items around except for a jar of skin cream. We’re promised that the beds will be freshly made. If we want a mosquito net, the price rises from 15,000 to 40,000 Franc (1,000 RWF = 0.70 €). We agree. A dinner can also be served. I emphasize that I would prefer only fully cooked food. Understood.

In my room, there’s no light; a new lightbulb is supposed to be installed. The man leaves, and we are told to lock the door behind us and not open it for anyone. After a while, he returns with a colleague, and they start working. I get no electricity, but I do get a mosquito net. A little later, fresh bedding arrives, and I must admit, I couldn’t make my bed with sheets as neatly as our host does. In the meantime, I make do with a bucket of water and a cloth to „wash“ myself. Eventually, the food arrives, steaming hot: beans, potatoes, pasta, and vegetables—and cheap, under 4 Euros when converted. Our hosts say goodbye. We had agreed that we would call when we leave the house for the key handover. To my horror, I realize that I’m still not marked on Legends Tracking as a checkpoint and discover that my tracker is turned off. How silly: What must the race observers be thinking?

Lars and I, in our wisdom, had already booked two rooms in a hotel in Ruhengeri, the location of the next checkpoint, where I would likely arrive just before dark.

I sleep somewhat poorly, as the mosquito net tries to do its job, but it can only do so much when mosquitoes are inside the net. I go on several „hunts“ and discover that the mosquito net isn’t new, but bloodstained, likely from other pests. Hopefully, my malaria prophylaxis does its job.

Day 2:

Gasange – Lake Muhazi – Byumba – Ruhengeri (CP2)

161 km/ 2500 Hm

Time in Motion: 11:23h

Elapsed Time: 13:51h

first my video day 2:

Around 5 o’clock, we set off again. Lars soon disappears around the next bend, while I roll very slowly downhill towards Lake Muhazi. The gravel descent demands my full concentration—there’s no way to call this „smooth.“ Stones, holes, ruts—the full package for getting thrown off balance with the slightest lapse in attention.

At dawn, I cycle along the lake. The morning atmosphere is wonderful.

I’m not alone, either—I keep overtaking heavily loaded cyclists on their steel-framed bikes, and some people are already walking.

I pass by the Kingfisher Resort. I couldn’t get a spot here. The reception is on this side of the lake, while the hotel itself is on the other side and can be accessed by boat. Next time, then…

A cycling team is standing by the roadside next to a motorcycle. A moto-taxi? No, the rider has a large wooden box on the back, filled with fresh bread. I grab some! Who knows when I’ll get food again?

At the next junction, there should be a shop. I need to refill my water. A lot of people are standing around, but the shop is closed. So, I move on. Now I’m riding on asphalt, but it’s still almost 30 kilometers to Byumba and nearly 1,000 meters of elevation gain.

I draft behind a steel-framed bike—a bicycle taxi, known as a „Boda-Boda.“ These are the affordable alternative in Rwanda, especially in rural areas. A ten-minute ride costs around 100 RWF, about 7 cents. These taxis are made from sturdy bicycles, often „Made in China,“ and adapted to carry passengers and heavy loads. A distinctive feature is the reinforced rear rack, often fitted with a cushioned seat for passengers‘ comfort. Many are decorated with colorful additions that the riders use to personalize their bikes.

My „riding partner“ has probably just dropped someone off in Byumba and is now on his way back. He falls behind on the incline—I suspect these bikes are single-speed—but on the flats, he keeps catching up, pedaling relentlessly. This goes on for many kilometers. We exchange a few words now and then.

I stop just before Byumba at a crossroads. Several bicycles are leaning against a beige-colored mud-brick building with a few chairs outside—a „restaurant.“ Can I get coffee here? Nope, but there’s cola and water. Food? One of the men disappears and returns with a paper bag full of chapatis, a type of flatbread. I take three. Others bring goat meat skewers, but I don’t dare try them.

Is there a toilet? No, but across the road… I decide to keep going and find a quick spot behind some bushes when the opportunity arises. But where can I find a place without onlookers? Here, where there’s barely a 100-meter stretch without people? I find a small ditch. Looking up and down the road—no one around. Below me, maybe 20 meters away, a group of women is cutting something. Thankfully, they don’t notice me. Just as I pull my cycling shorts back up, a moto-taxi approaches. Close call. I can’t imagine how awful this would be if I had stomach issues…

Onward to Byumba, and then I plunge into the descent. Gravel. And what a descent. I crawl at walking speed over eroded ruts and large stones.

At some point, two teenagers stand by the roadside. They greet me politely; I greet them back. Then, one of them suddenly jumps up and runs alongside me. He gets closer and closer. Suddenly, he reaches out, snatches something white, turns around, and sprints back up the hill.

Perplexed, I stop and watch him. He waves something in his outstretched hand and disappears behind the eucalyptus trees. What did he take? I check my food pouch on the handlebars. Aha—my wet wipes! Not exactly essential, but still crucial for daily hygiene, especially in the saddle area. Hmm… I probably won’t find replacements in Rwanda.

The next 75 kilometers of gravel roads are sometimes lonely, winding through a beautiful hilly landscape, sometimes so steep that I have to push my bike, and sometimes lined with people, especially children. Some sections are so steep that I have to push my bike. Thankfully, no one is chasing me this time. Kids usually run alongside unusual cyclists for long distances. „Good morning“ at any time of day or night. Today, they add a new phrase: „Give me money,“ „Give your money,“ or variations like „Put my money“ or „Put your money.“

A quick stop at a small shop, like the ones found in every little settlement. Sometimes these tiny stores are hard to recognize—the mud-brick houses all look the same, often with an open door and people gathered outside. But which one is actually a „shop“? I look around to see if other Muzungus are there, as they usually attract a crowd. Once again, I grab some water, pineapple Fanta, and a few cookies. The owner proudly poses his child for a photo. A gummy bear for the little one is met with a puzzled look.

The sky darkens. So far, I’ve been lucky, but I’m not sure when exactly the rainy season starts. The long rainy season should begin soon and lasts from March to May—bringing frequent and heavy rainfall. Is the transition even clearly defined? Either way, it starts to drizzle, and distant thunder rumbles. Oh no, I have a terrible fear of thunderstorms in the open.

I stop under a large tree—finally, no people around. Probably, everyone has found shelter from the rain. While putting on a thin rain jacket and short rain pants, I take a few bites of the bread I bought from the „flying“ (or rather, motorcycle-riding) vendor this morning.

Suddenly, out of nowhere, a slightly chubby girl in a gray hooded shirt appears next to me. She points at my bread and her belly, which isn’t exactly small. Hungry? I give her half of my bread. She snatches it, runs off laughing, and joins another girl walking nearby with an umbrella. I guess they were making fun of me. Slightly annoyed, I pedal on.

At least the drizzle stops. The road is a bit slippery but could be worse. But I spoke too soon…

A little later, I reach a small settlement and hear loud noise in the distance—like construction machinery. I expected this but didn’t realize it would hit me today.

Road construction! Massive trucks and excavators are at work. And I dive right in—ankle-deep mud instantly clogs my tires. I jump off and take a few steps. Immediately, I have 10-centimeter-high „heels“ of mud stuck to my soles. This will be fun. Pushing isn’t an option—I have to carry my 60-kilo bike for a few meters. At least there’s a firm path on the side for my feet.

Huge construction machines are everywhere, some carving away at the roadside to widen the road almost to highway size. Near them, a few yellow-helmeted workers sit casually in the shade, waving me and other travelers forward with little enthusiasm. I wonder if they even know what the machines are doing. I keep a wary eye to make sure I don’t get run over.

After a packed-down section, I breathe a sigh of relief—only to encounter the same muddy chaos a few hundred meters later.

Ahead, a RaR team is talking to a Chinese man—probably the site manager. They glance in horror at their navigation device. They tell me they’re looking for a detour—this 16-kilometer stretch is unbearable. At an average speed of 5 km/h, we’d be stuck here until midnight before reaching CP2 in Ruhengeri. Oh dear.

Then, another stretch of mud. One of the cyclists in front of me slips, can’t unclip in time, and crashes full-length into the red mud. Poor guy! I wobble cautiously forward.

A few kilometers of beautifully packed terrain follow, but then—more machinery noise in the distance, and the same ordeal repeats. I resign myself to my fate. Stop & go!

Suddenly, a barrier. Beyond it, a steep hillside with ominous sounds—rockfall! The guard waves me to stop. On the other side, heavily loaded steel bikes are being pushed uphill. Seems like there’s no barrier on that end.

I keep glancing suspiciously at my bike computer. The 16 kilometers should be almost up. And indeed, I approach a small village and a huge soccer field, where two teams, cheered on by a large crowd, are battling for victory. It seems the students have the day off for this event, as countless children in colorful uniforms are gathered around the field.

Shortly after, there’s a short but very steep climb, and I reach the asphalt road. The RaR 2026 participants will likely have to contend with 16 more kilometers of paved road.

Only about 30 kilometers to the second checkpoint in Ruhengeri. It’s going great. Smooth asphalt and fast descents interrupted by short uphill sections. I’ve definitely earned this. There are masses of people along the sides of the road. In the second row, the usual bikes with cargo or used as taxis. Then, lots of moto-taxis and some cars and large trucks. After speeding along, I only noticed a knee-deep, almost bathtub-sized hole in the asphalt at the last second. I slowed down and focused my attention more on the road. And then I realize: my bike looks awful. The color is barely visible under all the dried mud. It’s unlikely they’ll let me into the hotel looking like this. What to do?

Just before Ruhengeri, I stop at a gas station. It’s unclear whether there’s a car wash, but I ask anyway, showing the attendant my dirty bike. He points behind the building, where a small group is cleaning an SUV. Immediately, I’m surrounded, and everyone gets to work on my bike wash request. A Muzungu (foreigner) doesn’t come by every day. While three people focus on my bike, I suddenly feel something on my legs. What’s this? In front of me, a boy is kneeling and scrubbing my red, crusted skin with soapy water. What a service…

I pay my bill, a mere pittance, give a tip, and a few kilometers later, I arrive at CP1. I collect my guest gift, a small wooden gorilla keychain. It occurs to me that I didn’t pick up my gift at CP1 earlier—I simply didn’t know about it, or is that just an excuse not to carry extra weight around? Joking aside, a small, cute stuffed elephant will find its way to me at the finish line, replacing my little plush bear. Almost at the same time, Lars arrives. We eat something here and then head to the hotel. We had booked the same one the night before.

The warm shower is bliss, and the soft, cozy giant bed under a mosquito net is a real treat. I decide not to wash my clothes. It’s not that bad. This way, I don’t stand out too much, unlike if I were riding around as a „groomed“ Muzungu.

At the hotel—warm shower, soft bed, mosquito net. Heavenly.

Day 3:

Ruhengeri (CP2) – Volcano Belt – Gishwati Forest – Muhanga

167 km/ 3400 Hm

Time in Motion: 12:04h

Elapsed Time: 14:16h

In the morning, there is an early breakfast buffet just for us at 4:30 AM, featuring fruits, eggs, toast, jam, honey, and most importantly, coffee with milk. I guess I’m a bit of a coffee addict…

Today, we’ll be climbing above 2800m altitude twice. In total, over 3400 meters of elevation gain must be conquered, and the terrain is said to be quite challenging.

The first few kilometers are uphill but manageable on asphalt. From all directions, children in blue and colorful uniforms, holding notebooks, stream towards me, walking in the same direction. Ah, school must be starting soon. At some point, the schoolchildren begin coming toward me—I must have already passed the school.

In the distance, towering volcanic cones rise into the sky, illuminated by the newly risen sun. I am approaching the Volcano Belt. Less than 50 kilometers away, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, stands Nyiragongo—a 3,470-meter-high stratovolcano, considered one of the most active volcanoes in the world.

The road seamlessly transitions into gravel—an extremely rocky track. We had been warned that it would be a rough ride for hours. I hope I don’t get a flat tire. But no matter how eroded, full of deep washouts, or riddled with potholes the path may be, there are still moto-taxis here. They find the smoothest, best line, and often, we end up crossing paths, both searching for a rideable track…

After a short time of rattling over large, sharp, hardened lava rocks, my wrists start to ache—even with my Redshift ShockStop system on the stem. And there are still another 30 kilometers of this bone-shaking terrain ahead of me.

I keep having companions along the way. Apparently, not all children go to school, despite compulsory education. Just when I think I’m finally alone and breathe a sigh of relief before the next brutal climb, out of nowhere, a handful of kids suddenly appear and shuffle alongside me. Stopping to catch my breath or eat something? No chance. They talk, ask questions, demand…

I pass Markus, who is sitting on a rock by the roadside, having a snack. Around him, a swarm of children—no, a child-swarm. I slip past almost unnoticed and am left alone.

I’m looking for a secluded spot to disappear behind the bushes for a moment. I think I’ve found one, so I hurry before someone else shows up from somewhere. Pants down… and out of the corner of my eye, I realize I am not as unseen as I thought. In the curve below, a woman in a colorful dress, her hoe resting on her head, is watching me curiously. Hmm… oh well, it has to happen. Afterward, I ride past her with an embarrassed grin, offering a friendly greeting. Finding a place to relieve yourself in Rwanda? Nearly impossible. And of course, I don’t want to pollute this clean country…

Eventually, after what feels like a snail’s-pace descent over all those ruts and stones, we take a detour. Due to the escalating conflict between the Congolese army and the M23 rebel militia in the border area between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, we have to change our route. Originally, we would have passed through Gisenyi, a border town now at the center of these tensions. The conflict between Congo and Rwanda has been smoldering for years—fueled by disputes over natural resources and deep-seated ethnic tensions between the Tutsi and Hutu.

The new route leads slightly further south through the Gishwati Forest, one of the highest points of the tour at nearly 3000 meters.

As soon as I enter the next gravel section, I notice a change. People here seem poorer. Their faces often appear worn and hardened, and even adults sometimes ask for money. The houses look more modest, and more children wear clothes barely hanging onto their bodies. Many of them carry heavy loads.

By the roadside, I spot an incredible photo opportunity: in a stream, hundreds of bright orange carrots are floating, being washed by several young men standing in the water. I reach for my phone, but one of them signals—only for “money.” I keep riding—no photo then. I don’t want to take out my wallet in front of all these people…

The landscape is breathtaking—deep green everywhere, tea plantations lining the way. The incline becomes steeper and steeper until I have to dismount and push. I almost take the wrong turn, as the track appears to go straight up the mountain. Something isn’t right. I simply follow the road, and at some point, the path and my GPS track align again. Luckily!

The higher I climb, the more desolate it becomes. Finally, no people. The landscape now looks almost like home—coniferous forests and, further up, alpine meadows.

I can hardly believe it—after my long hike, I have reached the highest point. Here, I find a paved road. After countless kilometers of descent and several more long climbs, I won’t leave the pavement again until I reach my destination for the night: Muhanga.

On the way, I pass through wealthier areas again. Well-dressed men and women, on foot, on bicycles, or riding moto-taxis. Banana plantations, fertile land, and well-kept houses.

It seems to be market day in many places. People are carrying all kinds of goods—goats, chickens, pigs, banana bunches, corn cobs, pineapples, grains, buckets of mandazis (deep-fried dough balls), and much more.

I particularly felt sorry for a live pig, crammed into a narrow wooden crate on a bicycle and a dozen roosters, also alive, strapped to a wheel by their feet.

The afternoon wears on. A quick stop at a shop for a Coke and some water. At the bakery next door, I find delicious, freshly baked warm bread. I meet a few of our group here—Lars is among them. We agree to meet at the turnoff to Muhanga to search for our hotel, as the rooms were booked the night before.

Only 20 kilometers remain, but nearly 900 meters of climbing still lie ahead. Fortunately, the sun is no longer as intense. A truck passes me—clinging to the back is a Rwandan cyclist. Despite the obvious danger, I can’t help but envy him for a moment. Meanwhile, I have to haul myself and my over 20-kilo bike up the hill on my own.

The sun sets, and soon, darkness falls. I reach the intersection. After repeatedly overtaking each other throughout the day, Lars and I meet here again. We should be close to our destination—Muhanga, which lies a few kilometers off the main route.

The traffic is chaotic. The road is lined with potholes. Cars dazzle me with their headlights. I just hope the drivers behind us can see us. We get lost multiple times looking for our hotel. It’s not where Google Maps says it should be. We ask a policeman. He tells us we need to go another three kilometers.

Frustrated, we give up. Ahead of us is another hotel that looks decent. We ask if they have two rooms. Jackpot!

A functional warm shower, finally! I even wash my cycling clothes. After a delicious dinner, I sink into my fine bed under a mosquito-net canopy.

Day 4:

Muhanga – Kibuye (CP3) – Kirambo/ Kagano

149 km/ 2800 Hm

Time in Motion: 09:25h

Elapsed Time: 11:44h

I sleep poorly, lying awake from 2 a.m. The more I remind myself of the urgency of a good night’s sleep, the more awake I become. As every day, breakfast is at 4:30 a.m.—by the way, very delicious—and off I go. The plan is to first reach CP3 in Kibuye, on Lake Kivu, then continue to Kirambo without any gravel intermezzo. There are few hotels there, and Lars and I have booked two rooms 10 kilometers away at the Maravilla Kivu Resort.

I ride out of Muhanga in the dark, and Lars quickly disappears from my sight. I stop to check once more that everything is securely fastened on my „mobile laundry rack.“ Unfortunately, my „fresh“ clothes were still slightly damp in the early morning.

The asphalt road from the previous day immediately turns into a dirt track full of potholes just outside Muhanga, which soon transitions into a construction site. Above me, a red and green flashing light hovers. A drone in total darkness? Creepy. My mind starts racing: Am I being filmed? Is data being sent to someone with bad intentions? And sure enough, minutes later, four men suddenly appear in my headlamp’s beam, walking side by side and completely blocking the road. I snap out of my thoughts, and countless scenarios flash before my mind’s eye. I approach and squeeze past them, greeting them with a shaky, squeaky voice. They cheerfully return the greeting. I breathe a sigh of relief.

I can hardly see ahead of me. What’s going on? It’s foggy, and the damp droplets have fogged up my glasses. At dawn, visibility improves slightly. More people are now on the road, appearing ghostly from the mist.

I had already turned off my rear light, but Rachel (who will finish as the second solo woman a few hours later) informs me that I am barely visible in the increasingly dense fog. So, lights back on.

At some point, the wide dirt road transitions into asphalt, the fog lifts, and I begin my first „mountain.“ Almost 1,000 meters of elevation gain, with a moderate incline, but I can feel that my legs are not entirely fresh. With the increasing sunlight and no cooling breeze, every kilometer today feels like a struggle.

At some point, I overtake Lars, who feels the same way. But after every climb comes a descent, and it finally brings me rolling swiftly to the long-awaited Lake Kivu and the third checkpoint in Kibuye.

Lake Kivu is considered the most dangerous lake in the world. Its northern shores lie at the foot of the active Nyiragongo volcano. The depths of the lake contain vast amounts of methane, from which Rwanda generates a third of its electricity. However, if the magma chambers beneath it were to erupt, it could wipe out the two-million-strong city of Goma. A disaster similar to the one in Cameroon in 1986 could unfold. Lake Nyos, a crater lake, suddenly and unexpectedly released tons of CO2, suffocating nearly 2,000 people and countless animals within a 30-kilometer radius.

The shores of Lake Kivu are breathtakingly beautiful. I think of the article I read in Geo magazine. Surely, such a catastrophe won’t happen now, while I’m riding along here… Yet my thoughts keep drifting back to the eerie forces slumbering in the depths.

It’s blisteringly hot. My arms are lobster-red, and white blisters have formed on my wrists, despite frequent applications of sunscreen. I must say, the dark-skinned people around me are far more pleasant to look at than my sunburned „white“ skin.

Finally, I turn into the driveway to CP3, where Olivier from the crew greets me and leads me to the hotel. Breakfast is still available, with fruit, cupcakes, and scrambled eggs. I dig in. Lars arrives as well, and we commiserate about how exhausting the day has been so far. We both agree: no unnecessary extra kilometers. Lars checks with our resort to see if they can send a taxi to Kirambo, where we need to leave the route. They can.

After spending way too much time at the checkpoint, I finally have to set off. Less than 100 kilometers of asphalt remain, which should be doable before dusk.

The map suggests the route runs parallel to the lake—so probably flat, right? Wrong! The road follows the hillside, winding from one fjord to the next, constantly climbing and descending over hills.

Again and again, stunning views appear, sometimes with more, sometimes with fewer people. Around 4 p.m., school seems to be out. Suddenly, there are uniformed schoolkids of all ages everywhere, some stretching out their hands demandingly.

At a photo stop by the roadside, I see a dog approaching me—the only one I’ve seen so far in Rwanda. It’s visibly scared of me, making a wide arc around me.

Clouds gather overhead, and soon, it starts raining. Not heavily, but enough that I consider digging out my rain jacket. I also take the opportunity to remove my „laundry rack“—I don’t want my clothes getting wet again. I take shelter under a large palm tree and enjoy the chance to rest my legs.

On the next incline, a student in a beige uniform runs alongside me. He’s pushing an old mountain bike tire with a stick. To my surprise, wedged between the sidewalls is a tattered notebook or something similar. I ask him if he’s coming from school and if that’s his „school bag.“ He laughs and nods.

Below me, I see a training course with tire tracks, people maneuvering their bicycles and motorcycles around traffic cones. At the side, someone in a safety vest holds a clipboard. Apparently, not just anyone with a vehicle can transport people; they need a license.

I keep encountering people carrying loads on their heads or pushing stacked bicycles. I feel particularly sorry for a pig, tightly bound to a luggage rack.

The people here seem a little poorer, their clothes often torn and dirty, and only a few have smartphones.

As it gets steeper and I slow down, two bicycle taxi drivers pushing their bikes uphill get close to me—one on my left, one on my right. They aggressively call out, „Give me water!“ and try to grab my bottle. I shift gears and push on despite the uphill climb.

In some areas, people are friendly and cheerful, greeting me warmly. In others, I wouldn’t want to ride alone as a woman after dark.

Later, as Lars and I meet near the end of our day’s stage outside a small shop, I tell him about my earlier encounter with the men. He says he also had a bad feeling. We’re both relieved to be shopping together here. The roadside village looks unkempt, and the area is crowded. But we need water and supplies—tomorrow, as we head into the Nyungwe Rainforest, there will be nothing for kilometers.

The sun is still up as I arrive in Kirambo with Lars. He calls the taxi driver again. He’s on his way. In seconds, a swarm of children surrounds us. The police move us to the other side of the street since we’re causing an obstruction.

The crowd follows us to the other side. We are completely surrounded, barely able to turn around. Only when I pull out my smartphone or GoPro to capture the hustle and bustle does the crowd start to move. Apparently, they don’t like being photographed. But in my opinion, they’ll just have to deal with it if they’re going to invade our personal space like this. Half an hour passes, then another. Still no sign of the taxi. Another phone call—apparently, the driver is only just now leaving. The sun sets, and finally, a car pulls up. Yes, a car. Despite reassurances that it could easily fit two fully loaded bikes, that’s not the case at all. In fact, it’s questionable whether even one bike will fit, and if it does, there’s only room for one passenger in the front seat.

I pull a frustrated face—if only I had left an hour ago by bike. There’s no point in arguing; the car won’t magically get bigger, and I need to get going. Dusk has begun, and it will only take about 15 minutes before it’s completely dark.

I race down the hill; the resort is right by the lake. Seven kilometers fly by in no time, then I reach a turnoff. The road seems to lead through a peninsula extending into the lake, all the way to the tip. A sign: 2.8 km to the resort. By now, it’s dark, and I’m shocked at the road ahead of me. Large gray-black stones, some firmly embedded, others loose, cover the path. I jolt my way downhill, twice losing my 1.5-liter water bottle that I had stuffed upside down into my side pocket.

At times, riding is impossible—I have to push my bike. Lars messages me: „Don’t ride down there!“ At some point, the taxi driver comes toward me, offering to transport me for the last few meters. I pass him with a blank stare, still fuming. Eventually, I arrive at my destination and immediately vent my frustration at the reception. To calm me down, they offer me a fresh pineapple smoothie.

I ask right away if they can organize a pickup truck or something similar for 5 a.m. The way back would be a nightmare, and tomorrow’s route is already going to be challenging enough. They promise to arrange it.

My room—expensive, but absolutely beautiful. This is a place one should come for a real vacation. At dinner, I treat myself to Tilapia in tomato sauce, a fish farmed in Lake Kivu. Delicious, served with mashed potatoes and vegetables. Another pineapple smoothie. I sink into my super comfortable bed and finally have a good night’s sleep.

Earlier, Lars and I had booked two rooms in Kibeho, a small pilgrimage site.

Day 5:

Kagano – Nyungwe Rainforest – Kibeho

112 km/ 3000 Hm

Time in Motion: 09:55h

Elapsed Time: 11:41h

After a very delicious breakfast, our taxi is waiting for us. Both bikes are lifted onto the loading area. Lars wanted to ride in the back but at the last moment decided on a more comfortable ride in the front.

Then the jolting begins. We will take over 45 minutes for the 10 kilometers. The first stretch is at walking pace.

At our starting point from yesterday, it is still pitch dark. You have to get back on the route exactly where you left it. I get out and negotiate the price with the taxi driver—something that should ideally be done before the ride, but we didn’t pay much.

Then we lift the bikes off the loading area. Lars takes off right away. I notice that something seems different about my bike; the top tube bag looks oddly narrow. I open it: EMPTY! I check again on the loading area, where my malaria pills and a small packet of salt are lying. Did they fall out? Then where are the other things—my Snickers, Knoppers, the little bag of gummy bears, the nuts, and the dates? In short—my provisions for the lonely climb into the Nyungwe rainforest. All gone! My Keego water bottle is missing too, and as I check further, so is my small Leatherman. This can’t be happening.

I can’t find my rhythm in the first few kilometers and stop multiple times to check if anything else important is missing. Luckily, nothing else seems to be gone.

I try to understand what happened. There are two theories: either someone jumped onto the truck bed while we were moving at walking pace—Lars had noticed the driver looking into the rearview mirror multiple times. However, nothing is missing from Lars’ bike, and his bike was leaning against mine. Or, someone reached onto the truck bed from the other side in the dark while I was negotiating with the driver. My bike was within easy reach.

The fact is, I have nothing to eat and little water, and I feel completely thrown off. I can’t quite focus on today’s journey, even though Simon described this section as one of the toughest: potholes, rocky, muddy, likely a lot of hike-and-bike sections.

From the very start, I ride on the packed red clay soil. In the dim morning light, I even find a spot to quickly disappear behind a bush—a necessary opportunity. But there aren’t many people heading toward the national park. The nature is beautiful. Everything is lush green, birds are chirping, and twice a turquoise butterfly, the size of a hand, flutters past me.

The inclines are moderate, and it’s becoming more and more secluded. I really like that. Even though I have nothing to eat and my water is almost gone, I almost forget it because I’m so captivated by my surroundings. The path is flat, but I have to be extremely careful—again and again, there are small “bridges” made of irregular, very slippery wooden planks and muddy passages.

Then, suddenly, more people appear. There must be a village nearby. I turn the next corner and see Lars bent over his removed rear wheel by the side of the road. I hear something about his brakes not working properly. He will probably have to install new brake pads.

A short while later, the first mud-brick houses come into view. A man approaches me. What does he want? I look at him with a mix of curiosity and defensiveness. He asks if I need something to drink or eat and leads me to his nearby “shop.” Saved! I had nothing left to drink or eat. I stock up on bananas, cookies, cola, and water. The cola bottle has a slightly thicker body and can replace my missing Keego bottle in the bottle holder.

Once again, I pay only a small amount compared to prices back home and continue on my way. My route graph shows a dark red incline ahead. Oh no, time for some hike-and-bike.

And indeed, the climb is so steep on a damp, clayey, and slippery surface that even a moto-taxi has to let its passenger get off. I hike a few hundred meters, the ground is quite slippery, and I push my bike forward with all my strength. But soon, it flattens out again and becomes easier to ride. I marvel at the diversity of the vegetation, as we are well above 2000 meters above sea level.

A woman cycles past me. Is that Rachel? No, it’s Kate, whose teammate had dropped out. Rachel had started earlier in the morning, while my start had been delayed due to the hotel transfer. With this time advantage, Rachel will still reach CP4 but will have to ride the gravel section to Kibeho in the dark—but more on that later. I don’t waste any thought on these circumstances; my ranking is as unimportant to me as never before. What matters is finishing and bringing home beautiful pictures.

Faster than expected, I reach the asphalt road that runs through the rainforest. It is the only road and follows the border with Burundi closely. Every few kilometers, three heavily armed soldiers stand guard. It gives me an uneasy feeling, but after all, they are here for security. I stop briefly at the first group and ask if I can take a picture. No, of course not!

A little later, I experience firsthand that photography is really not allowed. I ride a few meters with a team—I think Dennis and Jorn. We take pictures of each other, them of me, and me of them. Just as they are riding toward me and I press the shutter button, a military vehicle appears around the curve, with a few armed soldiers onboard. I am still standing there with my smartphone in front of my face. The armored vehicle screeches to a halt right next to me. From the passenger seat, a stern face glares at me. He seems to be an officer of higher rank. I stammer that I only took a picture of the cyclists. I’m about to open my photo gallery as proof when they drive on. Phew!

A little later, I finally get my desired picture: behind a bend, several vehicles are parked—military and police. On the roadside, a large truck is lying on its side. I ride past and snap a quick photo backward. In that moment, I feel like a „disaster tourist,“ and a bit of guilt nags at me. At the same time, I am somewhat shaken by the shock of this sight. I ride on the left side of the road and suddenly wonder if that’s even correct… My brain must not be functioning properly anymore. I quickly move to the right side, as large trucks keep coming towards me.

Just 25 kilometers to the next town, and after some ups and downs, I reach Kitabi. My original plan was to spend the night here at the end of day four, but due to route changes caused by the conflict with the Congo, that didn’t work out, which would have consequences for the next day.

In a kind of fast-food place, I meet a few RaR riders. The food is displayed in chrome trays. I choose rice, pasta, vegetables, a type of spinach, and some fries, along with a Fanta Pineapple. I decide to skip the offered meat.

I discover a WhatsApp message from Lars. Unfortunately, he has to drop out—he can’t get his rear brake fixed. What a shame! Later, I read that he has reached Kitabi, will spend the night there, and is still trying everything to get his bike running again.

I set off again. And now, one of the most beautiful sections lies ahead. The lush green of the well-kept tea plantations creates a stunning backdrop, and I have to stop again and again to take photos.

Then, the route takes me through a fairly remote area, and the gravel road transitions from „smooth“ to quite rough. There are also some steep climbs. I have to push my bike several times.

A poorly dressed man with a stone on his head begs me for money. What if he starts chasing me? Unconsciously, I drift to the left side of the road. Suddenly, out of the corner of my eye, I see something bright green rushing towards me, and I just barely manage to jump aside. A bike—a „Black Mamba“—with a boy and a lot of cargo on it. He is speeding downhill, and who knows if his brakes even work. A crash would not have ended well for me.

Then, suddenly, asphalt again, and I roll towards Kibeho, a small pilgrimage town.

Right at the entrance, there’s a small shop selling souvenirs, Christ and Madonna figurines, as well as drinks and those fried dough balls. I buy a cupcake and a chapati along with a bottle of water. In front of the shop sits Dennis, waiting for his teammate, who is searching for accommodation. I’m still undecided whether I should continue riding to the next checkpoint. But in half an hour, it will be dark. Better to stay here—the hotel is already booked. Dennis gives me the final push to make the right decision: a friend of his strongly advised against riding the next gravel section in the dark.

I search for my hotel but don’t have the name or address and end up at the wrong place—a large pilgrim’s hostel. The room is huge, and there’s even a hot and working shower. I skip dinner at the hotel since I still have my pastries and an avocado that I’ve been carrying around for two days. Questionable whether it’s still edible, as this fruit is quite sensitive to pressure and has probably been through a lot in my bag these past days. But surprisingly, the green thing is intact and absolutely delicious.

Then, I roll down the mosquito net and head to bed. The hotel owner has promised to leave a breakfast package at my door and assures me that I can leave the house at three in the morning. Having learned my lesson, I ask multiple times to be sure.

With one last look at Legendstracking, I see that my actual booked hotel must have been just a few houses away—some of the „dots,“ as we call the location markers of riders on the map, were there.

Day 6:

Kibeho – CP4 – Kigali (finish line)

210 km/ 3450 Hm

Time in Motion: 14:28h

Elapsed Time: 16:35h

The alarm rings just before three. A little later, I’m out the door and almost trip over my breakfast, which is sitting on a chair in front of my room. A few hard-boiled eggs, cake, and bananas. What more could one ask for?

I say goodbye at the reception and step out into the cool night. The route first follows several kilometers of paved road. Out of nowhere, people keep appearing, caught in the beam of my headlight before vanishing again into the darkness of the early morning hours. There are bicycles on the road as well. Not a single one has lights. Eerie. You often hear a squeaking sound before my light catches the cargo bikes. According to Rwandan traffic regulations, this is allowed, but for us RaR riders, the organization requires front and rear lights.

My plan today is to have breakfast at CP 4 and then head straight to Kigali. I’ll probably arrive there quite late. I don’t even want to think about the entire route—over 200 kilometers and almost 3,500 meters of elevation gain. Worst case, I’ll have to spend another night somewhere along the way. But I’d really rather not.

First, there are 20 kilometers of asphalt ahead, followed by about 50 kilometers of gravel. The route will take me through a remote, wild valley with slippery trails—the very thing that stopped me from continuing yesterday. For now, my focus is on reaching CP4 around midday.

I set off. It’s nice to ride through the night without always being in the spotlight. After a few kilometers, I spot a man walking along the roadside in the darkness. As I pass him, I suddenly hear a rustling noise coming from my bike. Oh no, I have to stop. One of my bag straps has come undone and is brushing against the spokes. That could have ended badly. I fix the issue and glance back toward the man—he’s gone. He probably found our nighttime encounter just as unsettling as I did and made a wide detour around me.

A little farther on, a sudden “How are you?” comes out of the darkness. What a fright. And a bit further ahead, my headlight catches a group of cargo cyclists—riding without lights.

I meet Markus, and we chat for a bit. I tell him that I spent the night alone in the pilgrim hostel, while several other riders had found accommodation in a hotel a little further away. Markus tells me I wasn’t actually alone—he had ended up there too, after failing to find another place to stay. I hadn’t seen his dot on the tracker, though; he must have arrived after I had already fallen asleep.

Before the gravel section begins, I take a break for breakfast—maybe it will be light by then. Markus continues on.

But by the time I descend into the “wild valley” with its slippery downhill, it’s still dark. Just as expected, the path is treacherous, with deep ruts appearing again and again, demanding full concentration. By dawn, I reach the valley floor. The wide road eventually narrows into a single track.

Very lush and green, with lots of fields. Not many people are around, except for a few on their way to work.

I ride along without a second thought. Suddenly, a strange noise. It’s coming from my front wheel. I stop and spin the wheel—it makes a weird clicking sound. Is something wrong with the bearings? Is this the end of my ride? A thousand thoughts race through my mind. I’ve made it this far, and it would be such a shame to have to give up now. I take out the front wheel, but as someone who’s not exactly a technical expert, I have no idea what to do. As I try to put it back in—holding the bike with one arm and the wheel in the other—the heavily loaded bike nearly topples me over.

Just then, Markus comes by. Wait, when did I pass him? He stops and offers to help. Oh, gladly! I explain my issue—that there’s a strange noise—and spin the wheel after reinstalling it. He listens and says it sounds like something brushing against the spokes. At that moment, I see it—the cable from my hub dynamo had come loose from the guiding strap due to all the bumps. Such an easy fix, phew! Markus suggests taping the ends down for extra security. I do that, then continue riding.

Not long after, I get the chance to return the favor. One of those rickety bridges made of uneven wooden planks stands in our way. Markus has already unclipped one foot from his pedals and is trying to awkwardly cross the five-meter-long obstacle while half-sitting on his bike. Just then, his cycling shoe slips on the wet, rounded wood, and his left leg falls through the gap between two beams. The bike tips over on top of him. Stuck like that, he can barely move.

I grab his bike and pull it up, allowing him to free himself. Apart from a bleeding shin, he’s okay.

I decide it’s safer to dismount and carefully balance my way across the precarious structure.

About half a kilometer later, it happens to me: my front wheel slips on a slightly elevated grassy ridge, and I fall in slow motion, completely unable to stop it. I can’t unclip from my pedals in time due to the awkward weight distribution, so my shoes stay locked in. I quickly get up, brush the dirt off my legs and pants, and notice a group of wide-eyed children staring at me. With what must be a bright red face, I joke loudly, “Muzungu bum bum!” and ride off laughing.

For a while, I struggle to focus and keep finding myself in awkward situations, as if I’ve forgotten how to ride a bike. The path takes a sharp left turn and becomes more rugged, forcing me to push my bike a few times. Then comes the aha moment: I find myself in front of the much-talked-about suspension bridge, meant to help cross the wide riverbed instead of riding through the water. However, I notice that most people are taking the “direct route” straight through the shallow water. No matter—I have to at least see the bridge.

Thankfully, at some point, I regain my rhythm.

After several steep climbs under the relentless, burning sun, I reach the town of Gisagara earlier than expected and head to the hotel that serves as the last checkpoint. I don’t plan to stay long—there’s still a lot ahead of me, and the food options here aren’t exactly exciting.

Soon, I’m back on the road, diving into the next and second-to-last gravel section. The first 10 kilometers are a descent. Someone had mentioned that the final stretch from CP4 to the finish line would be “almost flat.” Yeah, right! One steep hill follows another, all under the scorching sun. At some point, I just don’t feel like climbing anymore. And honestly, I don’t feel like being around people either. I try to ignore the countless children along the way, all repeating the same demands. Fixing my gaze straight ahead, I ride on with tunnel vision, shutting everything else out.

Near a village, as I struggle uphill, about 20 kids start running behind me. I have a feeling they’re about to start with the usual “Put my money!” or “Give me money!” To distract them, I ask what they’re learning in school—maybe they can even count in English? And so, trotting behind me, we all count out loud together up to thirty. Then, I teach them how to count to five in German. It’s a really sweet moment. As I pick up speed on the downhill, I hear a cheerful chorus of “Bye-bye!” behind me.

Eventually, the second-to-last gravel section comes to an end, leading onto a wide, perfectly paved road. My Garmin acts up for the first few kilometers, showing my track parallel to the actual route, cutting corners weirdly. I start doubting if I’m going the right way and even backtrack a few hundred meters. I reload the route, and now it matches—relief! The traffic is light, and the climbs are manageable. My calculations tell me I won’t make it to Kigali before dusk, but I will get there today. The race organizers had changed the route just before the event, adding an extra gravel stretch up ahead that would slightly shorten the way to Kigali.

I suddenly remember I haven’t booked a hotel for the night, so I take a short break in the shade to sort out a room and grab something to eat. A group of RaR riders passes by, and I get ready to head out again.

Shortly after, I turn onto a reddish-brown gravel road. One last time, I find myself surrounded by people—especially children—probably just getting out of school. Eleven kilometers, I can handle that. But after 20 kilometers, I’m still on this road. Clearly, something went wrong with my notes. Eventually, though, I reach the very last stretch of gravel.

But what comes next is not fun at all. A relatively narrow road, packed with traffic. No surprise, I’m now entering the outskirts of Kigali. Luckily, I can use the hard shoulder, but it’s also full of pedestrians and unpleasantly bumpy. So I keep shifting back onto the road whenever my side mirror shows a clear path. Switching between the shoulder and the road is tricky because of the uneven ridge separating them. After nearly 15 hours of riding today, my concentration is definitely not at its peak.

As dusk settles, the road seamlessly transitions into a four-lane highway—heading uphill. I don’t feel safe here, so I climb through the bushes onto a parallel paved sidewalk. Some sections are crowded with people, others are empty. Sixteen kilometers to go. Then, it’s all downhill. I merge back onto the road, carried along by the thick traffic, with cars and countless moto-taxis zooming past me. It’ll be fine.

Then comes a roundabout. Traffic is jammed, and suddenly, I’m in the middle of it all. Insane! But the wave of red taillights carries me along and spits me out at the right exit.

Just two kilometers left—steep uphill. Lionel passes me, shouting something. One last sprint to keep my position? No thanks!

As I reach the entrance of Café Tugende—the finish line—I even stop to take a photo. By now, my competitor is long gone, and the finish line is all mine …

Relieved and victorious, I throw my arms into the air, then accept my finisher’s gift and a Skol Panaché—a Rwandan-style Radler. Just the night before, I had serious doubts I’d make it back to Kigali this early.

A tough, beautiful, and unforgettable journey comes to an end.

Summary:

- 110 starters

- Around 20 women (6 solo)

- 87 finishers

- 23 did not finish (DNF)

- Gabi: 3rd solo female finisher / 50th overall

- Maximum time: 163h

- Winning time: 57h 50min

- Gabi: 134h 41min (1 day before the finisher party) – avoided night rides, not only as a solo female rider but also to enjoy the beautiful landscapes.

Epilogue:

I am infinitely grateful to live under conditions that provide me with constant access to clean drinking water, sanitary facilities, a healthy and varied diet, and many other conveniences that make for an unburdened life.

My bikepacking experience in Rwanda was simply unforgettable! Stunning nature, breathtaking landscapes, and an incredible cleanliness that made traveling especially pleasant. On top of that, the warm and friendly people made every encounter special. A true adventure I would repeat anytime!

Plastic Waste in Rwanda: A Clean Success Story

Seeing trash along the roadside in Rwanda? Almost unthinkable. Maybe the occasional crushed plastic bottle, but otherwise—nothing. How is that possible?

Rwanda has taken strict measures against plastic waste. Since 2008, single-use plastic bags have been completely banned, and in recent years, this ban has expanded to include plastic straws, bottles, and packaging. The government enforces the ban rigorously by controlling imports, imposing fines, and promoting environmentally friendly alternatives. This policy has made Rwanda one of the cleanest countries in Africa, particularly in its capital, Kigali. Additionally, waste separation programs and recycling initiatives further help reduce plastic waste.

Moses‘ Energy Bars:

Before setting off, I picked up some local energy bars—wrapped in banana leaves. Delicious! And the best part? You can toss the packaging into the roadside ditch without worry.

Murakoze cyane, Rwanda – and especially Simon and the entire crew!!!