Via Vandelli – Versuch Nr. 1 …………………………… deutsch …. italiano

Originally, the plan was to ride the original Via Vandelli … originally …

(The Via Vandelli is a historic trade and military road built in the 18th century, connecting Modena with Massa. Strategically routed through the Apennines, it is now preserved as a hiking trail. More on its fascinating history can be found at the end of the text.)

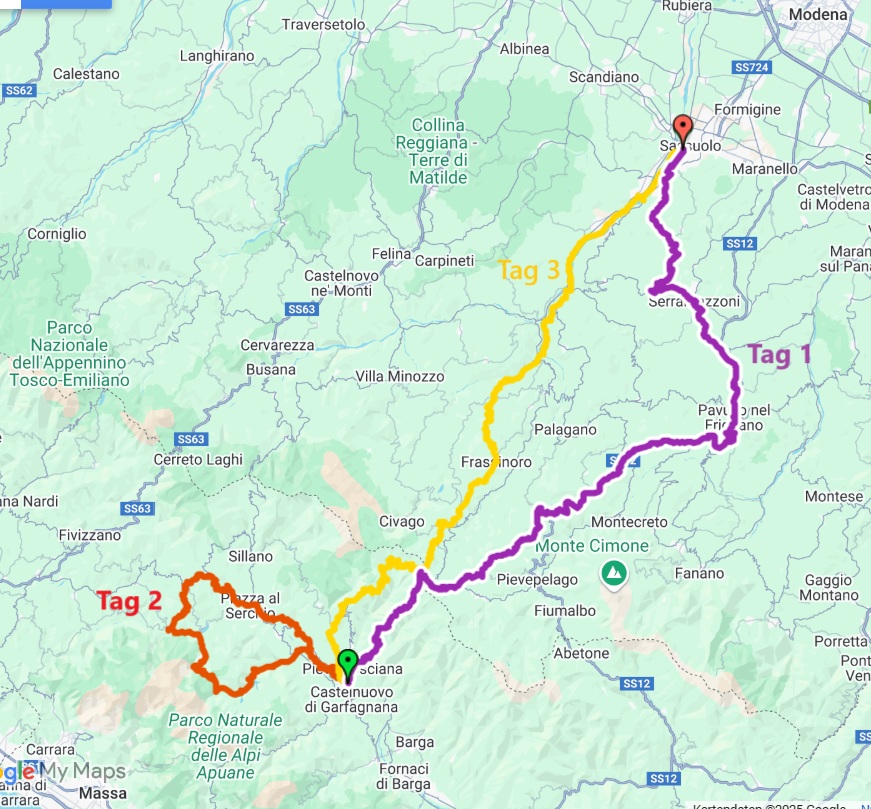

Our plan was to start in Sassuolo, follow the Via Vandelli to Castelnuovo di Garfagnana, and after an overnight stay at Hotel La Lanterna, set out early in the morning to cross the Passo della Tamburella. Upon reaching Massa, we intended to return the same day via the Passo della Fioba to Castelnuovo. The hotel was booked for two nights to accommodate this. On the third day, we planned to return via the Passo delle Radici.

But as the saying goes: A plan that can’t be changed is a bad one …

Or even better: A plan is there to know the way – but the art lies in cycling it flexibly …

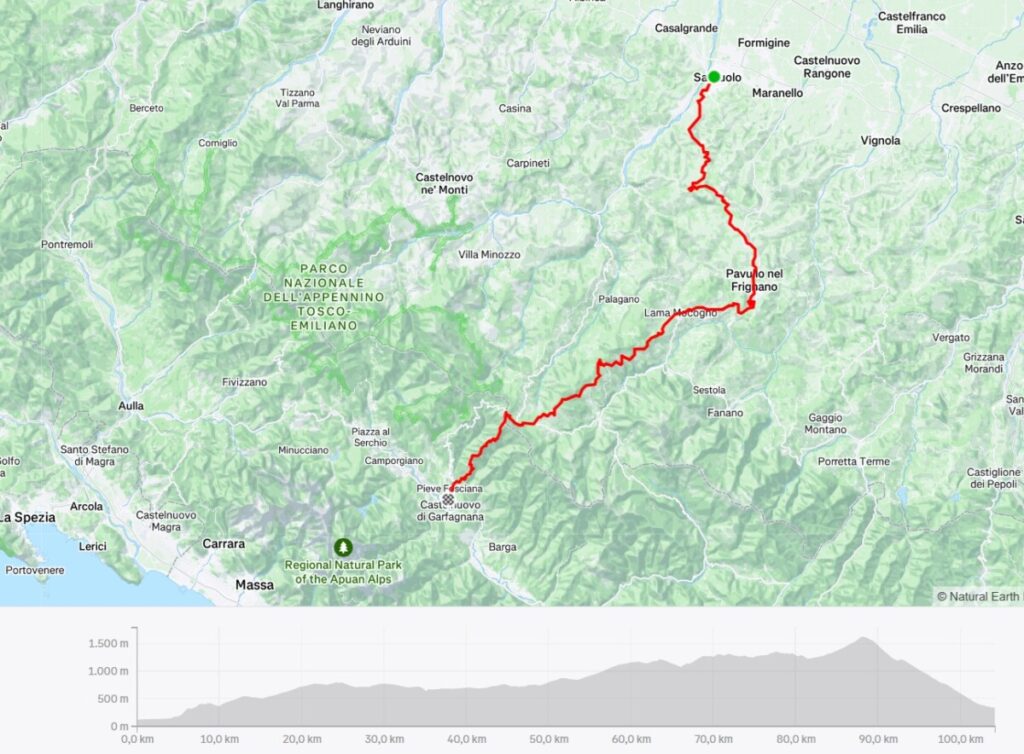

Day 1

104.20 km/ 2,710 m/ Movement time: 7:47:53

Strava

We leave the car in the small free parking lot behind the Palazzo Ducale and set off around 7 a.m.

After just a few kilometers and turning onto the first gravel section, our plan to follow the Via Vandelli is literally thrown out the window:

The heavy rainfall of the past few weeks has left its mark—fields and paths are saturated with water, making not only cycling impossible in some sections but even pushing the bike nearly unmanageable, as we sink ankle-deep into the mud.

On the first few meters of gravel, my foot slips, and I fall flat on the muddy ground. My entire left side is covered in mud, my hands are filthy, and I can’t even wipe myself clean.

I try to clean up (with little success) during our bar stop in Serramazzoni. Unfortunately, I’m so frustrated that I don’t even take a photo as proof—before and after don’t look much different anyway.

Up to Serramazzoni, we wisely stayed on the road, as it was immediately clear at every turn that the conditions were the same everywhere.

After that, we give the original route another try. But soon, we don’t even bother anymore—mud and water everywhere. Riding like this is no fun, not to mention the risk of falling.

Near Pavullo, the route first follows a bike path along the airfield, and then we skip the gravel again. It’s a shame because the route would have passed the famous natural stone bridge, Ponte del Diavolo, before reaching Lama Mocogno.

Only after La Santona do we decide to take a winding road up to Passo Centocroci and from there follow the original Via Vandelli route up to just before Passo delle Radici. The surface here is rockier and somewhat easier to ride on, but around every puddle, there’s deep mud.

The final stretch before Passo delle Radici is steep and covered in snow, so we switch back to the road. It also starts raining, so we continue rolling down the road to Castelnuovo di Garfagnana.

Our plan to cross the Apuan Alps via Passo della Tambura the next day will probably be out of the question. There’s likely still snow on the north side. This section also involves some bike-pushing—2 kilometers uphill to the pass. Then, it would likely be mostly on foot for about 6 kilometers down the spectacular, paved, almost terrace-like road until reaching more rideable terrain. I would have really liked to see this heart of the Via Vandelli, dating back to the first half of the 18th century.

The weather forecast doesn’t look great. So, we decide: since we haven’t been able to fully experience the first part of the route, we’ll postpone the crossing to Massa as well and “settle” for a day tour on this side of the main ridge.

Fortunately, we are able to clean the dirty bikes and panniers in the garden of the Hotel La Lanterna in Castelnuovo di Garfagnana.

Conclusion Day 1: Although we were off-road for less than a third of the route, our path was still very beautiful and, except for a few short sections, had very little traffic.

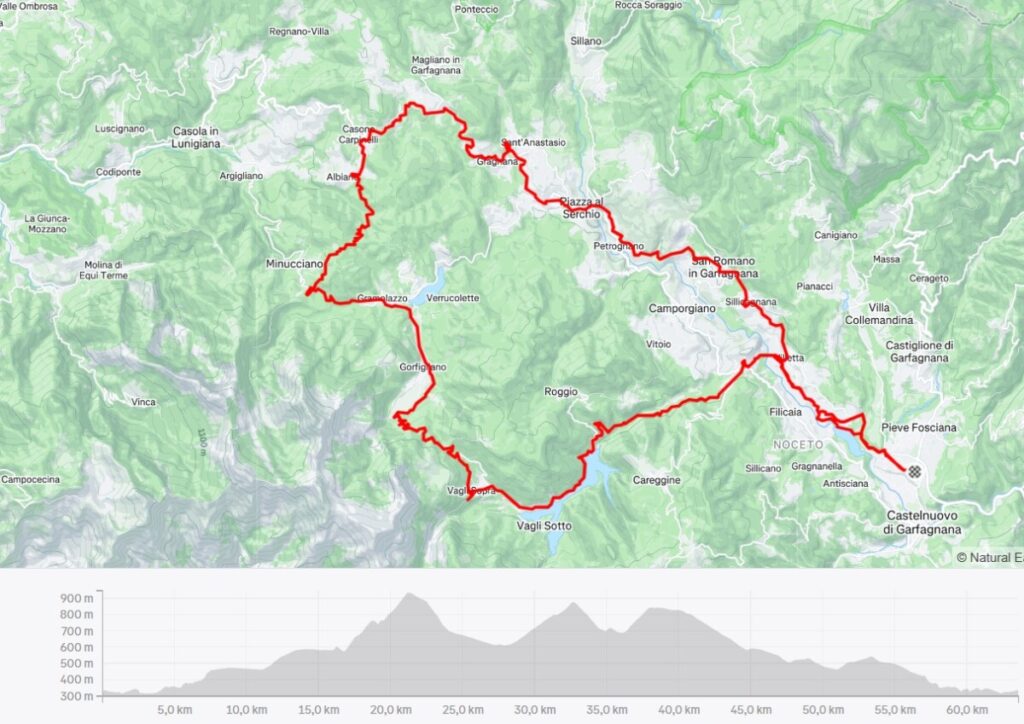

Day 2:

64 km/ 1,475 m/ movement time 4:35h

Strava

We decide to bike around the Garfagnana region for a bit. The Via Vandelli would pass by Vaglia di Sopra, and we want to head there first to perhaps catch a glimpse of the path toward Passo della Tambura. Further along, the route should take us over several small passes, past some lakes, and loop back to the hotel.

We start by following the original route along the shores of Lago di Pontecosi, which is dry, so we ride along the Serchio River instead. It’s a nice up-and-down on gravel (still very wet and slippery today, but not too muddy).

But here we encounter our first highlight of the day:

The Ponte della Madonna di Pontecosi. The bridge dates back to Roman times and has the typical humpback shape. Its name, „Pontecausi,“ gave the nearby village „Pontecosi“ its name. The wet stones make it extremely slippery.

Our second highlight comes a few kilometers later: the crossing of the valley via the railway bridge, Ponte di Villetta, along the narrow footpath next to the tracks. You should definitely not be afraid of heights, as the view down to the Serchio River in the middle of the bridge is a sheer 54 meters, and the railing isn’t very high.

The Ponte di Villetta, this 408-meter-long railway bridge on the Aulla–Lucca line with its 13 arches, was built nearly a hundred years ago, destroyed during World War II, and rebuilt in the 1950s. (Information from ChatGPT/OpenAI, 01.04.2025)

Then, we ride into the narrow valley toward Lago di Vaglia, a reservoir, at the end of which lies Vaglia Sotto. Originally, we had even considered spending the night here, as there’s a hotel in the village or the „Vecchio Convento“ next to the small Romanesque church.

Next, we head up to Vagli Sopra. We speak with a local who assures us there is still snow up top, as we do feel a bit sorry that we couldn’t make it over to Massa. The ruggedness of the peaks above us gives us a good preview of what we eventually want to tackle, but then starting from Modena.

We continue over a small pass to Lago di Gramolazzo. We were here about 10 years ago during the Randonnée, the 1001 Miglia.

Now, we could ride back to the hotel, but we decide to extend the loop a bit towards Minucciano. The nearly traffic-free little roads over two small hills are fun, even though it starts raining again and the wind picks up.

The return journey takes us through several small villages, passing Piazza al Serchio and San Romano in Garfagnana.

The idea of turning back onto the gravel route at the Villetta railway bridge wasn’t such a great one, as the new rain showers made the path even slipperier, so we take the Strada Provinciale for the last few kilometers.

A delicious dinner and overnight stay as usual…

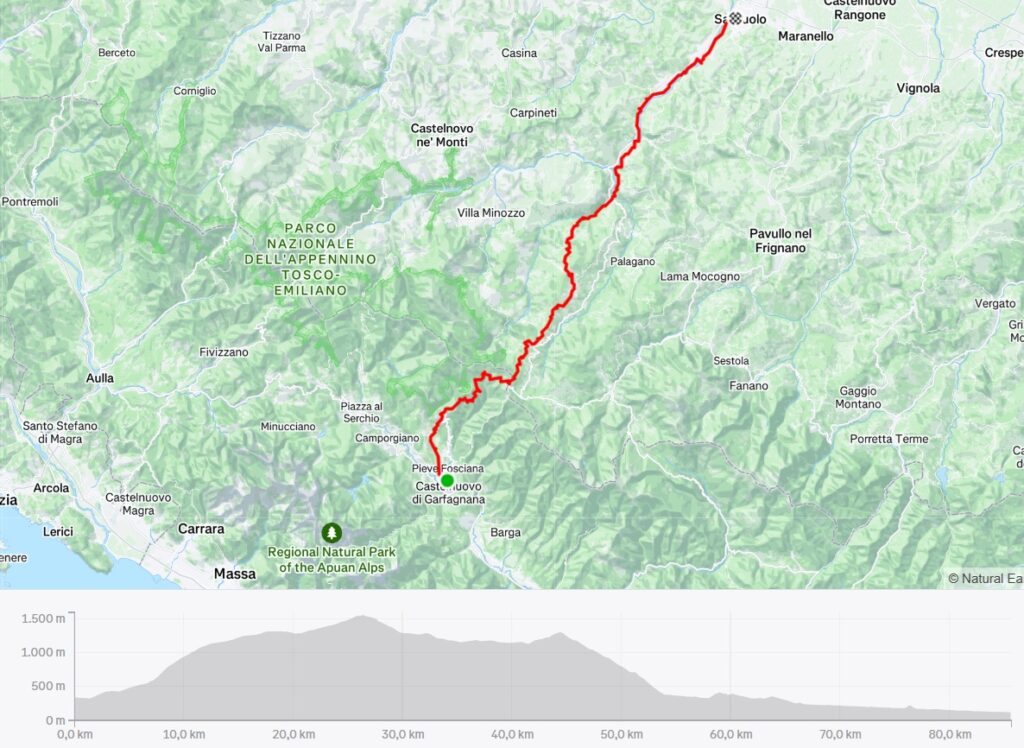

Day 3

85.65 km/ 1,867 m/ time 6:30h

Strava

When we wake up, a deep blue sky greets us. Why did the weather forecasts promise this only for the past two days?

Unfortunately, today is already the day to return to Sassuolo.

The Garfagnana lies between the Apuan Alps to the west and the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines to the east, so we have to cross the latter mountain range once again.

Ideally, we plan to go back over the Passo delle Radici, and for that, we choose a slightly steeper but scarcely traveled road, passing the medieval village of Sassorosso, which can already be seen from the valley, perched high above and seemingly merged with the surrounding rocks.

The nearly 1300 meters of elevation pass quickly with the view of the snow-covered mountains in front of us and the peaks behind us, which we would have loved to have crossed yesterday, seeming to fly by. The dense deciduous forests higher up are still almost in winter’s sleep. First spring flowers push through the decaying leaf layer from last year.

As I ride, I ponder how it’s possible that three asphalt roads meet at the Passo, including the ones we already know, yet we don’t have to descend on a familiar road. The solution—that the descent is not on asphalt—makes me a little uneasy.

And my premonition is confirmed: the path is still partially in deep winter sleep, meaning snow-covered, and where there’s no snow, there’s mud and similarly slippery terrain.

The estimated 7 hours to the destination probably wouldn’t be enough.

But then, we encounter solid ground again and roll alternately flat and downhill towards the east through the foothills of the Apennines. Behind us, the rugged, beautiful mountain landscape, and around us, beech, oak, and chestnut forests, interrupted by small fields, vineyards, and olive groves, all harmoniously blending into the natural surroundings.

Passing Frassinoro and Farneta, we reach the valley of the Dolo River, which further on flows into the Secchio River.

According to the plan, we should now have about 30 kilometers along the river, probably on bike paths. Bike paths? No!

At kilometer 58, shortly after crossing the Torrente Dragone, we head off-road. The hiking trail is pretty overgrown—looks like no one has walked here in a long time. If only we had read the signs correctly and rolled back just 2 kilometers, staying on a variant on the opposite side of the valley on safer terrain…

We thought we could try going a little further, after all, we can always turn back…

Thorn vines get caught in my clothes, trying to hold me back, but I ignore this sign as well. A bit further, the path is still rideable. A few sticks in the way give us the feeling of mastering the Bunny Hop. And then, a small ditch. The rainfalls from the past weeks (or maybe years?) have caused the terrain to wash away. We help each other lift our loaded bikes a few muddy meters down and then back up on the other side of the small stream. Then we continue; now the ground is alternately covered with leaves, and then we sink into the mud again. Within no time, the original color of our bikes is unrecognizable. Turn back? According to the map, it’s not far to the end of this gravel section. So, onward!

The next obstacle: another stream, but thick branches lie crisscrossed over the water. It’s not easy to balance over them, the pedals and saddle keep getting caught in the branches, and our dirty bike shoes are at risk of slipping. Made it! Now, turning back is absolutely out of the question.

I try to scrape off the mud from my bike shoes with a stick. If I had only known how pointless this action was, I would have saved myself those few minutes.

I already have a bad feeling when I see Hermann a little higher up on the path, pushing his bike. Ahead of us is a slightly larger stream, or rather, what the stream has done to the terrain: a V-shaped trench. About 10 meters below the overhanging edge is the harmless trickle of water, with the steep walls seemingly impassable. Hermann says maybe further up it’s passable. He’s already a bit below the edge, his ankles buried in the wet soil. Oh no!

My shoes sink just as quickly when I drag my bike down a bit further. Then over the water and up the other side. A glance upwards suddenly fills me with fear: What if the water-saturated soil gives way? What if the high earth walls collapse and carry us away in a mudslide? The ground gives way beneath my weight. With great effort, I manage to heave my bike over the edge. Made it!

But the way we look: covered in mud from head to toe, our shoes buried under a thick layer. I can’t even clip into the pedals anymore.

I just hope we don’t encounter another obstacle like that. But the next trench is harmless, and a few more times we have to push through the mud. But at this point, I don’t really care. I also don’t care what people will think…

Soon, we reach the supposed bike path. Of course, it’s closed. And, of course, we ignore the closure, climb over the barrier, and happily ride along the Secchio River. Trucks probably use this road during the week. After another three kilometers, we reach the actual bike path. It’s also closed, with a sign warning of “pericolo,” danger, which, once again, we “overlook.”

The path along the river is very nice, with fine gravel. It’s strange that we haven’t encountered a single person. Then suddenly, we can’t go any further. The bike path ends. In front of us is a roughly 5-meter wide, raging stream. What now? We push our bikes toward the mouth of the stream, where the current is weaker. We wade knee-deep through the icy water. At least the shoes are (almost) clean now.

From here, there are still 13 kilometers on an actual, permitted bike path to Sassuolo.

Conclusion of the day: We definitely went over the planned time, but it was an adventurous day… even if at times, it didn’t feel that fun… And cleaning the mud-covered bikes, bags, and shoes wasn’t exactly enjoyable either…

Tip to avoid obstacles on the last 30 kilometers: Once you reach the valley floor at km 56, I recommend crossing the Dolo River at the bridge, then taking the bridge over the Secchio at Cerredolo and staying on the orographically left side of the river until Lugo. There, you’ll rejoin our route (around km 66). Even better, stay on the road for a few more kilometers until km 73 to avoid wading through the Rio Lucenta. It doesn’t look like the bike path will be repaired anytime soon. After this river crossing, you can safely stay on the bike path, which will take you all the way to Sassuolo.

A detailed description of the original Via Vandelli and an interesting overview of its history can be found on the DAV website: „Mountain biking across the Apennines.“ (in german)

History: The Via Vandelli is a historic trade and military road that was built in the 18th century to connect the cities of Modena and Massa in northern Italy. Its name comes from Domenico Vandelli, a geographer and engineer who planned the construction under the rule of Francesco III d’Este, Duke of Modena.

History of the Via Vandelli’s Creation

In the 18th century, the Duchy of Modena needed direct access to the sea to facilitate trade and become economically more independent. Francesco III d’Este wanted to create a strategic route connecting his duchy with the port of Massa.

Francesco III d’Este sought a road that passed only through his own territory to avoid paying tolls to other states. Being dependent on trade routes controlled by neighboring states would make the duke vulnerable to extortion. As a result, he was forced to choose a route that crossed the Apennines.

Construction began in 1738 and took several years to complete. The route passed through the Apennines and the Apuan Alps, which made the work particularly challenging. The road was built with switchbacks to ease steep sections. Stone slabs and bridges were partially installed to make the path more stable. Despite innovative construction techniques, the road was often difficult for carts and goods to travel on. (Source: ChatGPT/OpenAI, 01.04.2025)